Displacement Displaced: Drawing on the Past

- By Mary Griep

- Paper and Presentation for 2018 Architecture, Culture, and Spirituality Forum

- View or Download as PDF

In 1998 I accompanied a group of students to Europe for a month. I took along 100 small pieces of paper for drawing and found myself deeply inspired by medieval architecture. These small drawings evolved into what has become a 20-year project of large-scale drawings inspired by 12th century buildings. This love of global medieval architecture has immersed me in many issues raised by preservation of cultural heritage. I have shared in the dismay over the tremendous number of sites, monuments and objects destroyed, removed, or significantly damaged since the year 2000. This destruction has been caused not just by political acts, terrorism, vandalism and acts of war, but also by fire, flooding, tsunamis, hurricanes and global warming. It seems overwhelming, but it is actually difficult to determine if the pace of loss has significantly increased, or if we are just more aware of the accumulation of loss.

Whether or not cultural heritage is disappearing at a greater rate in the 21st century, there is clearly reason for concern, given the worldwide scale of destruction and the seemingly widespread goal of some fundamentalists to oppose the very notion of cultural heritage. Looting and the often-shady nature of the antiquities market is an age-old problem that is accelerating. In2008 Forbes Magazine ran an article touting antiquities as the new growth area of investing.(Crawford, Fallen Glory, 565.) Currently, ISIS is reported to be granting permits to looters of ancient sites taking a hefty cut out of the proceeds to support their troops. Some of the destruction has political and religious roots, but much comes through ignorance. A recent example is that of the despoliation of ruins of ancient Babylon. During the Iraq War the US and coalition forces built military Camp Alpha on the ruins of ancient Babylon, using soil rich with antiquities to fill sand bags and bulldozers to create anti-tank trenches.

Even how we talk about what is being destroyed has become contentious; the term cultural patrimony seen as problematic given the gendered nature of the term. Issues such as who defines what belongs on the list to be protected, on-going arguments against “saving the past” and currently most fraught, who “owns” this past (and the attendant costs associated with use and preservation) have stirred controversy. This debate contrasts the preservation minded, art historical, globalist view, against a more modernist view that values the regional or local. Mark Jarzombek in Art and Globalization, puts forward a provocative argument saying that while the Eurocentric, art historical view values the past, seeing itself as the inheritor of a long classical tradition, many other countries moved from being a colony, to a nation-state, to a call for local and regional identity, not tied to the European classical tradition, which prompts them to value a history that is “a form of resistance to both the earlier ideas of national modernism and the growing specter of globalization.” (Jarzombek, Art and Globalization, 191.)

This clash between the nation-state with ties to a classical past versus societies who are re-creating ancient subnational, ethnic and religious borders from within is a process that has been gaining traction since at least the fall of the Berlin Wall, bringing attention to a wide variety of world views that fall outside the Eurocentric paradigm. The Buddhist concept of impermanence does not particularly value preservation, or see an old stupa as having more merit than a new one. Saving an old building, such as Mohammad’s home in Mecca, is seen by the regime in Saudi Arabia as idolatry. Therefore, the Wahhabis see the destruction of the house as analogous to Moses destroying the golden calf. Much destruction has also come from the view of holy sites as infidel or possessing objects whose very presence is polluting, corrupting, or merely extraneous to the group currently in power. There are many who argue it is the very forces of late capitalism with its desire for porous borders and globalization that are fanning the fires of destruction.

Clearly this debate is not new. In the 19th century John Ruskin saw the rebuilding of antiquity as futile and even wrong-headed. In The Seven Lamps of Architecture he states, you need to “Look necessity full in the face, and understand it on its own terms…pull the building down… do not set up a Lie in its place.” Ruskin’s argument against reconstruction/rebuilding comes from his view that what the Lie destroys is “the spirit of the long dead workers, the connection of the passing years to each other, the witness to deeds and suffering, the mystery of receiving a gift from the past.” (Vigderman, The Real Life of the Parthenon, 32.) This is a clear precursor to Walter Benjamin’s theory of the aura of a work of art dwelling only in the original that cannot be mechanically reproduced. Its unique physicality must be experienced. Both Ruskin and Benjamin articulate the value of the original as participating in an ongoing narrative. It is this ability of certain sites and objects to enlarge the viewer and to tie her or him to a larger context, beyond the often-fleeting nation state or political alliance that is most often mentioned in discussions of why we try to preserve the past.

The globalist or universalist view of heritage has fueled what has been a rapidly expanding culture of museums since the early 19th century, including more than 700 sites worldwide designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Patricia Vigderman in her book, The Real Life of the Parthenon does a marvelous job of explicating the conflict between those who would argue that objects and sites are best appreciated and understood in their local contexts and those who argue that it is more democratic to offer a wider range of access and cross cultural context in encyclopedic museums. This contentious discussion has led to a push for repatriation of artwork opposed most vocally by the British Museum in its defense of retaining the Elgin Marbles, taken from the Acropolis of Athens in 1805. The museum’s rationale for keeping them is centered on the assertion that the British Museum is not an art museum; it is rather a museum of culture and as such is meant for the whole world. They see themselves as inheriting the European Enlightenment, “Keeping alive the light of curiosity about ourselves and others, the world. A bulwark against narrow nationalism and careless despoliation.” (Vigderman, The Real-life of the Parthenon, 32.) Joan Connelly, classicist, argues the other side, saying, “The universality of art is a pernicious concept, more interested in the object than the maker or culture “an “impetus for ‘cultural strip mining.” (Vigderman, The Real Life of the Parthenon, 49.) Her concern is with the preservation of sites and objects as sources of scientific knowledge, careful preservation and respect for local meanings.” (Vigderman, The Real Life of the Parthenon, 49.) She articulates the call for cultural coherence, placed against the arguments for wider access and placement of art into a global context.

I find compelling arguments on both sides of the debate over where art belongs. My art loving soul thinks that art loses something when taken and placed in context with other geographically and culturally disparate objects. I cringe at the reproductions of famous monuments, that lead to what Jarzombek has termed the “globalized bureaucratization of space, not to mention the heritage-ization, touristification, and global UN-ification of culture.” (Jarzombek, Art and Globalization, 193.) Yet my more democratic side points out the underlying elitism in the view of art as “belonging” to a specific locale. While I have been incredibly fortunate to be able to visit much art in its “home” and revel in its aura, this is a privilege afforded few. Kwame Anthony Appiah speaks eloquently for those who may never be able to travel, yet whose lives are changed and enlarged by their experience with works of art in museums. And organizations, including the British Museum and the Getty Trust, have provided much needed protection for objects endangered in their place of origin.

Projects inspired by the art historical, globalist and deeply Eurocentric push for preservation can be seen worldwide. In the aftermath of the shock over the destruction of Palmyra, a complex plan was devised to “save” its monumental Arch of Triumph. The Institute of Digital Archaeology smuggled thousands of 3D cameras into Syria to record the site. Photos taken by locals and copies of tourist photos, provided data used to build a 2/3-scale digital model. Cement was made to approximate the density of the original stone, which was then precisely carved by robot stonemasons in Tuscany’s Carrera marble quarry. Once in London’s Trafalgar Square it was assembled, followed by display in New York’s Times Square, and Dubai. The intention is to eventually erect it close, but not in, the ancient city of Palmyra in honor of Khaled al-Assad, the art historian executed in there. (Crawford, Fallen Glory, 564) The fact is it could be “reprinted” and put anywhere. There could eventually be more than one.

Many of these current projects rely heavily on digital technologies, particularly photography. Michael Ignatieff in The Russian Album says “Yet so swiftly does time move now that unless I do my work to preserve memory, soon all that will be left…is photographs, and photographs only document the distance that time has traveled; they cannot bind past and present together with meaning.” (Ignatieff, The Russian Album, 48.) This is my fear; that what we are preserving digitally is a document of time passing, while in contrast a building or object can preserve a complicated sense of place and people. Deep study or an actual experience of a place has the possibility of making one aware of the sheer amount of human attention that has been focused in this spot, in contrast to the existing, overwhelming amount of random digital information, which has made focus less achievable in daily life. If it is so easy to consume the digital format, the ephemeral, the entertaining flickers, do we slow down enough to engage in a dialogue? I think not, it is not a medium conducive to contemplation. Another vexing issue is cost. A project like the re-creation of the Arch of Triumph from Palmyra cost $143,000 to install in London raising the issue of who pays and who decides which places or things are worth reproducing.

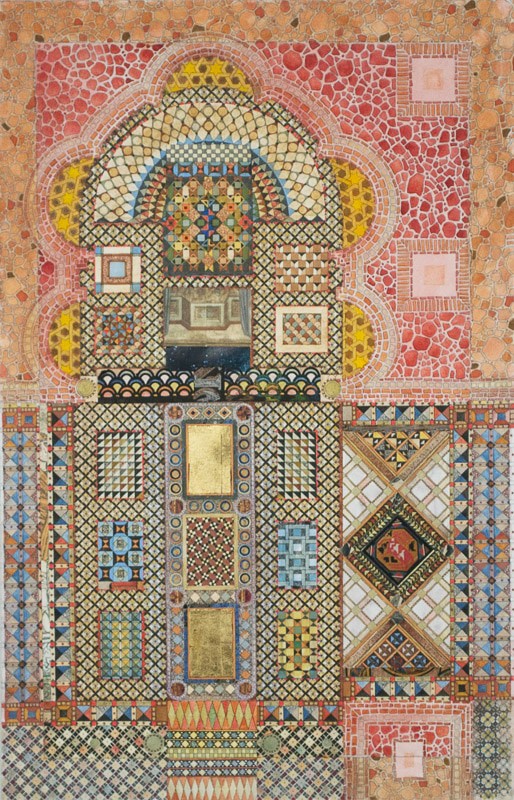

The longer I have worked on this paper, the more realize that I, as a practicing artist, have most sympathy for the localists, a fellow traveler with Walter Benjamin, who would have us appreciate the site, or the real object. And Patricia Vigderman, who argues that drawings or other deep studies of sites done at close range over a long span of time can carry at least some of the aura of the original. She asks whether perhaps at least some of our “reverence for the monument, in fact, depends on much later work of retrieval: on a partnership between past and present, on the participation of later imaginations in its reconstruction.” (Vigderman, The Real Life of the Parthenon, 31.) My drawings are of 12th century sites that still exist, though the passage of centuries has compromised their legibility. My spending one to three years researching and drawing per site are a recognition of the difficulties inherent in trying to tease out coherence from a site that has been reimagined and reconstructed many times.

I have come to see my drawing project as one of participation in a centuries long conversation. These sites have been “chosen” as it were, over and over again. Many people, over long time periods have had to choose to do the work, to spend the time and money to preserve them. On some levels I see the sites as being outside the discussions that try to reduce heritage to a political statement or an illustration of one particular worldview or theory. The surprising fact of their continued existence connects us to a larger narrative. These places were built to last, unlike so much of our current environment. They embody history. In Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino says, “The city, however, does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of the streets, the gratings of windows, the banisters of the steps… every segment marked in turn with scratches, indentations, scrolls.” (Calvino, Invisible Cities, 11.) Calvino’s words apply just as evocatively to a sacred site. There is no short cut to really observing and synthesizing. While many visit a site just to check it off a list, and pass through without ever engaging deeply, those who take the time and are open to the experience, can come away with a new view of the world or themselves. They are the visitors who spend more time and take fewer photos unlike the hasty viewers who also rush through museums, where the average time spent in front of a work of art can be measured in seconds.

This April I returned to Chartres, the site of my first drawing in this series. To mark the 20th year of the project it seemed fitting to return to see how my first attempt at a drawing based on imaginative rebuilding would correspond to the actual site. To return there and see the magnificent restoration was shocking at first. I had spent two years drawing the 1998 version of the building, yet time had not stood still; the cathedral has been under almost continuous restoration. Most surfaces have been cleaned of the centuries of dirt, smoke and incense and repainted as you see here. It has been controversial, as there are those who more value the romantic dark atmosphere of the ages. While the interior was surprising, I found in my time there the new interior lightness grew on me. It seems especially beautiful on cloudy days, of which there are many in central France. I was also reminded that many of these places, whether designated UNESCO sites or not, remain a living part of the community. Benjamin says that sites develop meaning as part of a locality, “for its current inhabitants as well as to those who come in search of the past (Vigderman, The Real Life of the Parthenon, 79.) On Sunday I was there for an ordination, and the cathedral was decorated with fresh flowers, family and friends were there, it was incense filled, and the organ music was transporting. Yet sadly, as an important religious site that is part of an active pilgrimage route and therefore, a possible terrorist target, it was often ringed by armed soldiers. It remains a valued and sacred place, one that has carried meaning since before the Christian era. It is a site with an ongoing story. And as such seems eminently worthy of being examined yet again. The texts describing the townspeople helping to build it, the care needed for removal of the windows to avoid their being casualties of war, all help me see this place as a monument to human attention, and my time spent in drawing as an homage to the time of all those who came before. I hope that viewers will take away some sense of the complexity of these old sites and a vision of something larger than current preoccupations. And as an artist I hope that drawings and other reproductions of these places are not all we leave to the future.

References:

- Arches Project

- Bezeklik Cave Temples Restoration Exhibit

- Brotton, Jerry. A History of the World in Twelve Maps (Penguin Books, 2012).

- Calvino, Italo. Invisible Cities ( Harvest HBJ Book. 1974).

- Crawford, James. Fallen Glory: The Lives and Deaths of History’s Greatest Buildings (Picador, 2015).

- DeLillo, Don. The Names (Knopf. 1982).

- “A Place of Safe Keeping? The Vicissitudes of the Bezeklik Murals”.

- Ignatieff, Michael. The Russian Album (Elizabeth Sifton Books, Viking Press. 2001).

- Jones, Lindsay. The Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture: Experience, Interpretation, Comparison (Harvard University Press, 2000).

- Majdalani, Charif. Moving the Palace. Translated by Edward Gauvin. (New Vessel Press, 2017).

- Lowenthal, David. The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge University Press, 1985).

- Vigderman, Patricia. The Real Life of the Parthenon (The Ohio State University Press. 2018).

- Mark Jarzombek, “Art History and Architecture’s Aporia”. pp. 188-193. In James Elkins, Zhivka Valiavicharska, and Alice Kim, eds. Art and Globalization (The Pennsylvania Sate University Press. 2010).

Partial list of sites significantly damaged or destroyed since 2000:

- 2001 – World Trade Center, New York – planes flown into by Al Qaeda.

Buddhas of Bamigan, Afghanistan – dynamited by Taliban. - 2003 – Palazzo Fremanx, Malta – demolished by government.

National Museum of Baghdad – acts of war.

Ancient Babylon, Iraq – acts of war.

Much of Baghdad, Iraq – acts of war. - 2004 – Libraries of Iraq – acts of war.

Duchess Anna Amelia Library, Germany – accidental fire.

Libraries destroyed by Indian Ocean tsunami in Indonesia, Malaysia, Maldives, Thailand and

Sri Lanka. - 2005 – 218 medieval Christian churches destroyed by 2005 – contested attribution.

Hurricanes Katrina and Irene destroyed numerous historic sites. - 2006 – Moscow, Russia. Between 1917 and 2006 640 notable buildings destroyed – various reasons.

- 2010 – National Cathedral, Port-au-Prince, Haiti – earthquake.

- 2011 – Civil war in Libya – many important sites destroyed.

Egyptian Scientific Institute – looted and destroyed – civil unrest.

43 Shia mosques – Bahrain destroyed by government. - 2012 – Maldives – Islamists destroyed all Buddhist and Hindu antiquities.

Much of Timbuktu destroyed –

Aleppo, Syria – 2012-16 much of city destroyed – acts of war. - 2013 – Ahmed Baba Institute, libraries of Timbuktu.

Libraries of Fisheries and Oceans, Canada – burned, dumped and given away by government.

Christian Churches – Bohol, Philippines destroyed. - 2014 – Al-Omari Mosque, Gaza City, Palestine – airstrikes.

Saeh Christian Library, Lebanon – burned.

National Archives of Bosnia and Herzegovina – burned by Bosnian rioters.

ISIL forms Kata’ib Tuswiyya to select targets for demolition. UNESCO terms it “cultural cleansing”.

Between June 2014 and February 2015 ISIL plundered and destroyed at least 28 historical religious buildings.

Book burnings Mosul, Iraq and Anbar Province – ISIS.

Glasgow School of Art, Scotland – accidental fire.

Saudi destruction of historic sites in Mecca and Medina ramps up.

Coast Miwok Indian Burial Group removed to build housing development – USA. - 2015 – Palmyra, Syria – destroyed – civil war – ISIS.

Dharahara Shrine, Nepal – earthquake.

Statues in St. Petersburg, Russia destroyed by vandals.

Institute of Scientific Information on Social Sciences, Moscow – fire and water damage.

Mosul Public Library destroyed – ISIS.

Mzuzu University Library, Malawi – accidental fire.

Sufi Shrines, Tripoli, Libya – destroyed – ISIS.

Beginning of movement to dismantle Confederate Monuments – USA. - 2016 – National Museum of Natural History, New Delhi, India – accidental fire.

Central Italy – many churches destroyed by earthquake. - 2018 – Church of St. Lambertus, Germany – demolished to make way for surface mine

- 2019 – Norte Dame of Paris – partially destroyed by fire.

- At least 31 UNESCO World Heritage sites currently threatened by climate change.

Selected projects underway to save cultural heritage

- American Historical Association

- Arches Project: Collaboration between Getty Conservation Institute and World Monuments Fund.

- Bezeklik Cave Temples Restoration Exhibit

- “A Place of Safe Keeping? The Vicissitudes of the Bezeklik Murals”

- The British Museum with Google

- Culture and Creativity

- The Getty Conservation Institute

- Global Heritage Fund

- International Centre for Heritage Preservation (CICOP)

- International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions

- International Council on Monuments and Sites

- Institute for Digital Archeology

- Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage

- The Legacy of Ancient Palmyra

- Rebel Architecture

- Unite4Heritage Project

- UNESCO

- World Monuments Watch List